Although the eight-part Netflix series directed by Sanjay Leela Bhansali is visually spectacular, the grandeur is somewhat muted by its many soap operatic elements.

From start to finish, Heeramandi feeds on luxurious otherworldliness. It seems as though Sanjay Leela Bhansali, who is directing his debut series for streaming services, is urging us to long for the big screen even more. A prostitute named Mallikajaan in Lahore, defeated and encircled by destiny, sobs in front of a fireplace and throws priceless jewelry into the icky fire. Ghostly shadows cover the entire estate. A voice cries out and the curtain opens, revealing the haveli on the other side, its interiors a flurry of activity and laughing. Through the combination of light and shade, it conveys more than any plot twist or beautiful phrase, making it a captivating point in the series.

Heermandi is full with poetic verse. As usual, and no doubt spurred by the location and era, pre-Independence India, Bhansali expresses his admiration for the greats of Urdu and Sufism. Sakal Ban, a song that heralds the approach of spring, is based on a poetry by Amir Khusrow and features references to Ghalib, Mir, Zafar, and Niyazi. Similar to Rekha in Umrao Jaan (1981), Alamzeb (Sharmin Sehgal), one of the main protagonists, is an aspiring poetess. There are conversations that are almost hard to tell apart from verse. Alamzeb threatens her fiancé, “I will serve you couplets for breakfast and poems for lunch.” She may just as well be speaking to the audience.

Alamzeb is the daughter of Mallikajaan (Manisha Koirala), the exclusive brothel’s mistress at Shahi Mahal in Lahore’s Heera Mandi pleasure area. Another daughter of Mallikajaan is Bibbo (Aditi Rao Hydari), a celebrated singer-turned-revolutionary spy. The Raj is facing increasing resistance in the 1940s. For protection and titles, the immaculate nawabs work for their foreign conquerors. However, the true decision-makers are the courtesans, who can bring their patrons to disaster while also protecting their secrets.

The show opens with a series of intense flashbacks. As it turns out, Mallikajaan is hiding a horrific atrocity from her past with the help of the depraved nawab Zulfikar (Shekhar Suman). When discovered, it sparks a rival courtesan named Fareedan (Sonakshi Sinha), who infiltrates Heera Mandi and begins to tease out both new and old feathers.

The story revolves around Fareedan’s intricate plans for retaliation, an uneasily developing romantic relationship between Alamzeb and Tajdar (Taaha Shah), a young, rebellious nawab, and the agitation of the revolutionaries. Jason Shah’s villainous police superintendent Cartwright prowls the area looking for bones. It takes time for Bhansali and his writers to weave the many threads together. Even with the spotless sights and sounds available, the wait gets lengthy. The exciting political landscape of the time is depicted in general terms, which doesn’t help (the Muslim League and the call for an independent Pakistan state are not mentioned).

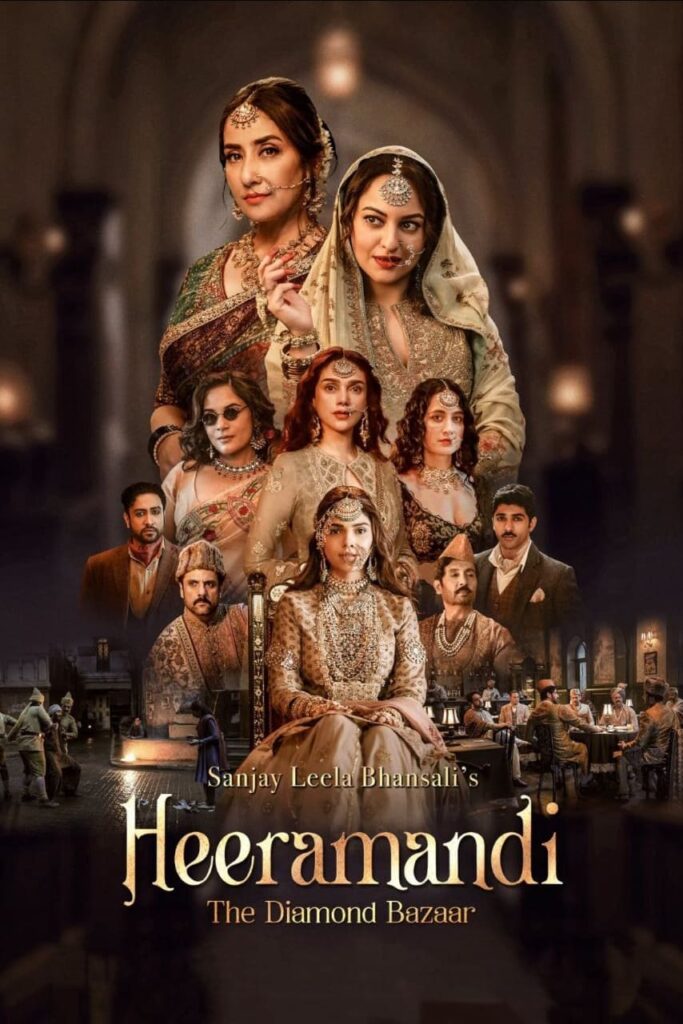

Heermandi: The Bazaar of Diamonds in Hindi Sanjay Leela Bhansali is the director.

Cast: Fardeen Khan, Taaha Shah, Sharmin Segal, Sonakshi Sinha, Aditi Rao Hydari, and Manisha Koirala

Eight episodes; 45–65 minutes in length

Narrative: The power struggles and intrigues of courtesans in India during the Indian Revolution

Heera Mandi, a real neighborhood in Lahore, dates back to the Mughal era. Over the years, its courtesans have accumulated significant money and power. The history of tawaifs supporting the liberation movement is fascinating (Bibbo’s character, for example, seems to be based on Azizun Bai, a Kanpur courtesan who battled the British during the 1857 insurrection). However, Bhansali and his writers frequently overreact emotionally when highlighting these unsung heroes, drawing clumsy but well-intentioned comparisons between the characters and India during British rule. Zulfikar makes fun of Mallikajaan for using the “divide and rule” tactic. According to Bibbo, we resemble birds in a golden cage, just like India is a golden bird in an imperial cage.

The title character in Gangubai Kathiawadi (2022), portrayed by Alia Bhatt, fought for the respectability of prostitutes in Mumbai during the 1960s. Heeramandi’s dancers and singers are often suspected of engaging in prostitution; the performance tactfully acknowledges this facet of courtesan life. While running a tight ship, Mallikajaan publicly defends her own. She argues in court for the kothas’ elevated social standing as centers of culture and refinement. Even Fareedan, at her most evil, reacts to her peers with compassion and unity.

Heeramandi, which was filmed on an enormous budget, is breathtaking to see. The series (whose four cinematographers are Sudeep Chatterjee, Mahesh Limaye, Huenstang Mohapatra, and Ragul Dharuman) is a winner for its compositional mastery and lighting trickery. Aside from paying heartfelt homage to beloved films like Mughal-E-Azam and Pakeezah (the twirling dancers on rooftops seem like they belong in Kamal Amrohi’s movie), Bhansali also makes a fleeting reference to KL Saigal, the actor who originated the character of Hindi Devdas, a role that was later carried on by Shah Rukh Khan in Bhansali’s 2002 film.

As the nawab Wali Mohammed, Fardeen Khan emanates a kohl-eyed menace, and Koirala gives Mallikajaan her body and soul, teasing remnants of humanity from an exaggerated part. As the chatty attendants Satto and Phatto, Nivedita Bhargava and Jayati Bhatia are hilarious. Working her high and hearty laugh, Richa Chadha is given a role that is far too brief. The show may have continued with more established actors like Chadha and Sanjeeda Sheikh, but Segal and Shah’s bland portrayals of the main lovers take up the most of the running time. Heermandi delves into Bhansali’s signature gothic abstraction for the last episodes. The women of Heera Mandi rush the streets in the climactic climax, a wave of protestors carrying torches storming a fort. The ending of Padmaavat (2018), in which throngs of women clad in ghoonghats plunged into a pit of fire and sang of freedom, is being aggressively reversed by Bhansali.